in memoriam Bertold Hummel

Commemorative speech on 27 November 2025

Professor Elisabeth Gutjahr

Dear Mr President, Dear Christoph,

Dear Councillor Mack,

Dear guests,

Dear Hummel family,

It is quite unlikely to be born on 27 November. These last days of November, the first days of the zodiac sign Sagittarius, have the lowest birth rates worldwide, and today, of all days, two great composers are celebrating their birthdays. Both were born in Swabia (or Baden, just a few kilometres away), one grew up in a Protestant rectory, the other sat on the organ bench with his father as a boy and listened. His first concert experience of a Bruckner symphony became a key moment for the eleven-year-old Bertold, who decided to become a composer. Bertold Hummel would certainly have spent his birthday, which is now 100 years ago, making music, as he did his whole life and that of his family, even though one of his six sons, the "black sheep", became a clergyman rather than a professional musician. Perhaps he simply took a kind of "shortcut" to direct dialogue with God, who perhaps loves music more than any other art form. Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, according to the second commandment, but perhaps the divine is ultimately sound: everywhere and gracious, and as a temporal art form, transcending time into the beyond of fading away.

In an age of increasing secularisation, the creative and also the post-creative artist has the task of pointing his fellow human beings to the transcendent, to the inexplicable and also the unprovable. The language of music – perhaps the most universal of all – is of particular importance here. Bertold Hummel, 2001

Bertold Hummel and Helmut Lachenmann, who are only ten years apart in age, trace the broad spectrum of artistic musical imagination and critical engagement in their musical works – including the catastrophes of the 20th century. Both are united by a deep sense of responsibility, justice and spirituality.

When I had the privilege of getting to know and appreciate Bertold Hummel personally in the early 1990s, it was not only his vast experience and professional expertise that impressed me deeply, but above all his attitude towards the world as a community. His constant willingness to take every person seriously and value them as individuals, recognising and discovering talent in everyone, was admirable. At that time, he was the jury chairman at the first European Rhythmics Competition at the Trossingen University of Music, and I was fascinated by how he was able to transform the rigorous competition into a kind of celebration with cheerfulness and goodwill, without deviating one iota from his performance standards. I was in my early 30s at the time, a novice in the field of competition management with an international jury. As I gave my welcoming speech on the large stage of the concert hall, I could feel my heart beating very clearly and heard the slightly tense sound of my voice. But Bertold praised this performance with the words: "You'll be rector here one day." A sentence that only came back to my mind years later. His student, the composer Jürgen Weimer, was rector in Trossingen at the time. The acumen with which he knew how to masterfully position a politically critical stance, the mastery of his rhetoric, which he knew how to use as a weapon against stupidity and intellectual laziness, were legendary; the radical nature of his aesthetic imagination also shaped his leadership style as principal. To experience both of them together – teacher and student, both long-respected principals – as they encountered each other with familiarity and at the same time with strangeness, challenging each other and at the same time acknowledging each other with respect, was a gift, still a precious memory today, instructive and deeply human. When asked by a journalist: Would you sacrifice an idea for a pleasant sound? Bertold once replied unequivocally: I would not do that. Helmut Lachenmann and Jürgen Weimer would probably agree with this answer.

Bertold Hummel spent his childhood in the Black Forest, and began his schooling in the cosmopolitan city of Freiburg im Breisgau. His family enjoyed making music and engaging in lively discussions, and they took a critical view of political events. Bertold was 13 years old when the Second World War broke out. Klaus Hinrich Stahmer writes in his notes on Bertold Hummel (in ‘Komponisten in Bayern’):

"...The aspiring musician had to accept personal setbacks when his long-standing involvement in house music with a respected Jewish family in Freiburg was denounced. At the age of eighteen, he was drafted into the Reich Labour Service and, six months later, into military service..."

Bear in mind that we are talking about 1943, at which point the war had already been raging for four years and Germany had long since been fighting a losing battle. Furthermore:"Late in French captivity, he sees his first chance to make music after all and actively helps to found a camp band consisting of a string quartet, woodwinds, trombone, trumpet, saxophone, accordion, piano and percussion. Here, his first string quartet was performed, along with popular works from Wagner's "Grals-Erzählung" to classical overtures and light music. Fellow prisoners built the missing double bass according to his specifications in the camp carpentry workshop, and, oh wonder, it "sounds" good! After five adventurous escape attempts, he succeeded in 1947 in returning to his homeland via Belgium and Luxembourg, where he first completed his school education in a repatriation course at the University of Freiburg with his Abitur (A-levels). I am sharing this passage with you, dear guests, because it tells us so much about the personality of our honouree: about his outstanding will to survive, his trust in God and his unconditional desire for music and making music, even in a prison camp. A black-and-white photo from that time shows Bertold Hummel sitting at the cello next to eight comrades from the camp band "Erich Horn". They are all wearing camp uniforms, and in the background you can see a wooden barrack, a kind of barn.

In 1947, Bertold Hummel returned to Freiburg, which, as one of its first measures after the Second World War, had already founded a music academy in 1946. Today, we can only imagine the atmosphere of that time. Bertold Hummel speaks of a "catch-up euphoria of the returning generation". Freiburg is located in the French occupation zone, so the returnee and musician experiences exhibitions by Chagall, Braque, Léger, Picasso and Rouault, but also a performance of Olivier Messiaen's Quatuor pour la fin du temps. His years of study, during which he took cello lessons from Atis Teichmanis, chamber music lessons from Emil Seiler, conducting lessons from Konrad Lechner and composition lessons from Harald Genzmer, had a formative influence on his entire life. He immersed himself in the musical universe of the Second Viennese School, encountered the music of Igor Stravinsky as well as the musical-aesthetic universe of Luigi Nono, and combined these experiences with his great passion for the Western tradition of church music. In 1981, Bertold Hummel summarised this as follows in a grand aesthetic credo:

I feel kindred in my thinking to A. Berg and O. Messiaen. The "cantus firmus" thinking of P. Hindemith and my teacher H. Genzmer, as well as their spontaneous joy in making music, have always impressed me. My teacher Julius Weismann captivated me with his impressionistic sound imagination, harmonic richness and formal diversity. I have never considered myself an avant-gardist! I have always followed the experimental attempts of my colleagues with great interest and have made use of one or two solutions in my own work. I see the possibility for our current situation to intellectually process the diverse insights – quasi in a synthesis of the many different stimuli that are available. My love of tradition and meaningful (subjectively speaking) progress has always shaped my musical language.

After completing his studies, Hummel took up a position as cantor at St. Konrad near Freiburg, but also played regularly as a cellist with the Southwest German Radio Symphony Orchestra in Baden-Baden and at the municipal theatres in Freiburg. His skills as an arranger and composer were increasingly in demand. As early as 1952, his "Missa brevis" op. 5 was included in the programme of the Donaueschingen Music Days. He met Inken while playing in a string quartet, and they married in 1955. With the violinist and teacher, who was born on the island of Sylt, he was able to share and realise his great passions throughout his life: music and making music, community and family, trust in God and confidence. Florian, Cornelius, Martin and Lorenz, the first four of their six sons, were born in Freiburg.

In 1963, Bertold Hummel accepted a position as composition teacher at the Bavarian State Conservatory of Music in Würzburg, where he and his family found a new home. In the following ten years, until the State Conservatory was transformed into Bavaria's second music academy, Hummel did truly pioneering work. He provided new music with the space it needed to flourish, facilitating encounters and experiences: he invited colleagues such as Korn, Genzmer and Hába to Würzburg, as well as Karlheinz Wolfgang Rihm, Peter Eötvös and Helmut Lachenmann. He headed the Studio for New Music for 25 years.

Pressing space problems were solved in 1966 with a new building in Hofstallstraße with teaching and concert facilities. This gave Würzburg's musical life a new centre, supported by the conservatory and its friends' association, which hosted concerts with high-ranking artists. The new concert hall was inaugurated with Bertold Hummel's 2nd Symphony 'Reverenza'. In 1968, a scholarship enabled him to spend six months at the Cité des Arts in Paris, which is celebrating its 60th anniversary this year and now offers over 300 residencies annually. Enriched and inspired, Hummel returns to Würzburg, where, after a short transitional period, the institution is upgraded from a technical academy for music to a Bavarian music college in 1973. Bertold Hummel becomes a full professor and head of a composition class. When Hanns Reinarzt steps down from the college management in 1979, his deputy Bertold Hummel takes over as president. From then on, he devoted himself with equal commitment to his composition class and the development of the conservatoire. With wit, cosmopolitanism and a courage to embrace diversity, he contributed significantly to the flourishing of the institution. For him, art and education were not two separate camps; on the contrary, musical education meant lifelong learning, something so self-evident for an artist that it hardly seemed worth mentioning. A pre-college ensemble is just as valuable as the world stars of the big stages. The real encounter takes place in and through music. Successful composers such as Jeff Beer, Ulrich Schultheiß, Claus Kühnl, Klaus Ospald, Jürgen Schmitt, Rolf Rudin, Horst Lohse, Jürgen Weimer, Hermann Beyer, Christoph Weinhart, Armin Fuchs, Tobias M. Schneid and Christoph Wünsch, the current president of this institution, form an impressive gallery and command attention. Bertold Hummel is their mentor, enabler and promoter, companion and critical friend.

In 1987, Bertold Hummel handed over the office of president to his successor in order to devote himself entirely to composing. The Würzburg University of Music appointed him honorary president in recognition of his services and with great appreciation. Hummel is at the zenith of his career: in 1982, he is accepted as a member of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts, followed by the Federal Cross of Merit 1st Class in 1985 and the Culture Prize of the City of Würzburg in 1988. Further awards follow.

On the occasion of the 1300th anniversary of the mission and martyrdom of the Franconian apostles in Würzburg Cathedral, Bertold Hummel composed the oratorio "Der Schrein der Märtyrer" (The Shrine of the Martyrs) based on a text by Bishop Paul Werner Scheele. A breathtaking, full-length work for five soloists, mixed choir, boys' choir, narrator, three organs, percussion ensemble and large orchestra, it was completed and premiered in 1989.

I knew Bertold Hummel as a sensitive, ever-curious man who approached the world with a smile. He had a dance-like lightness about him and sometimes gave the impression of being constantly on the move. He enjoyed a warm friendship with his namesake Franz Hummel, although the two were not related. On behalf of the Regensburg Chamber Opera, I wrote the libretto for Franz Hummel's An der schönen blauen Donau (On the Beautiful Blue Danube) based on a text fragment by Ödon von Horvath (Die Lehrerin von Regensburg, eine wahre Geschichte/The Teacher from Regensburg, a true story). Bertold was moved by the fate of Elly Maldaque, a young, popular, single teacher who bravely and courageously stood up for her convictions against a society that was becoming increasingly radicalised in the 1920s. Because of her political views and possibly due to denunciation by an admirer whose advances she rejected, she was dismissed from civil service without notice in 1930 and committed to a mental hospital. Shortly afterwards, she died there of heart failure. The chamber opera premiered in Klagenfurt and was performed in Regensburg. Franz Hummel and I quickly agreed: We dedicate this chamber opera to Bertold Hummel. Allow me to take a brief detour into the present – Bertold Hummel would certainly have been actively involved in today's day of action by German music academies against the abuse of power. Perhaps in reference to the resistance movement of Persian women, the Würzburg University of Music has given its day today the impressive title: Art.Power.Humanity.

As a composer, I feel committed to the community in which I live. My aim is to make a modest contribution to the effort to make the world a more humane and liveable place. The triangle of composer, performer and listener is a constant challenge for me: I have always found the l'art pour l'art viewpoint alien to me.

110901 – Ideas for the Future is the title of a composition for solo percussion and speaker ad libitum, written after "Black Tuesday", which went down in history as nineleven . The above quote can be found in the publisher's announcement of the work. Composer-performer-listener, this imagined triangle (ideally an isosceles one) has occupied Bertold's mind for many years. Composer-performer-listener as equal contributors to the creation of music. This image can be read as stages, but also as an open field. The listener who seeks out the composer whose work fascinates him and lives on in him; the composer who writes for a performer whose artistry inspires him and from whom he wants to learn; the performer who addresses a special audience or commissions a composition, and so on... The more I delve into this image and try to illuminate it, the more I become aware of its dynamics and potential for development. Bertold Hummel has taken on this triangle as a challenge. Questions of responsibility, relationships, meaning, community in this world – for one another – and beyond this world are the driving force behind our actions and thoughts – and this is what brings us back to the here and now: Art.Power.Humanity.

Perhaps two years before his final departure from this world, Bertold Hummel and I happened to meet for a long walk together. We talked about life and lifetime as a form, perhaps even as a musical form, and about our possible sense of this form. He then said that he knew full well that the arc of his life was already drawing to a close, but that this knowledge did not cause him any concern. Ultimately, everything was fine.

Thank you, dear Bertold Hummel.

Salzburg, November 2025

In memory of Prof. Bertold Hummel (1925–2002)

An obituary

Dr Thomas Daniel Schlee

in memoriam

In memory of Prof Bertold Hummel (1925-2002)

An obituary

On 9 August 2002, our dear friend, the composer and Chairman of the Music Advisory Board of the Guardini Foundation, Bertold Hummel, died in Würzburg. When he was presented with the Art and Culture Prize of the German Catholics by Bishop Karl Lehmann in the State Chancellery in Mainz on 13 June 1998 (together with Petr Eben), I said in my laudatory speech:

"What happiness to be able to talk about an artist whom you love and revere in equal measure, whose personal aura has touched you as much as his work! What a pleasure, too, to give a laudatory speech in honour of a composer who has spent his life independent of cliques, i.e. groups which, in the course of the tough distribution struggle, are also said to have an influence on the awarding of prizes (including their assessment by the media)... So today we are honouring an independent artist; and yet, the service is an essential characteristic of his work.

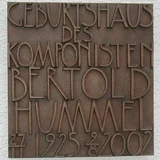

Bertold Hummel, born on 27 November 1925 in Hüfingen, Baden, was a student of Harald Genzmer in Freiburg im Breisgau, of whom he still speaks with great affection today. Aha, the 'insiders' will conclude in a flash: Hindemith in the third generation. Francis Poulenc would have replied: 'That's quite something'; but it is by no means enough to describe the scope of Hummel's oeuvre.

in 1997, his third symphony op. 100, 'Jeremiah' (inspired by Franz Werfel's novel), was premiered. Hummel gave me the immediately released CD with the remark so characteristic in its lack of insistence: 'Well, perhaps you have time to listen to it I was accordingly unprepared for the force and depth of the sounds of this great, important work. What colours in the harmonies and orchestra! What density of form and, at the same time, what clarity and distinctness of sound! Something similar can be said about Hummel's full-length oratorio 'The Shrine of the Martyrs' for soloists, two choirs, narrator, three organs, percussion group and orchestra, which was composed in 1988. This work seems to me to be a threefold sounding portrait: on the one hand, it summarises the composer's diverse expressive possibilities in an extremely happy way; on the other, it is a homage to Hummel's long-time place of work, Würzburg; and last but not least, a demanding work of art is placed here in the service of a spiritual message, which for this artist has always been a matter of the heart and his culture.

This is an essential point: Bertold Hummel's extensive oeuvre - his liturgical compositions, of course, but also his instrumental and orchestral music - repeatedly shines forth his religio, his connection to the spirit. Just as Hummel's spiritual message can be found in works intended for the concert hall, i.e. works of art, he also demanded the same artistic quality from liturgical music. He formulated his ideas on this emphatically as early as 1979 in his remarkable lecture 'On the situation of music in the church today'.

But back to the alert, sensitive musician Bertold Hummel, who is always on the lookout for new sound combinations: I am thinking, for example, of his subtle trio for flute, oboe and piano 'In memoriam Olivier Messiaen' - for me the link from the spiritually inspired to the composer's numerous works, which were formed, as it were, from an 'autonomous' artistic will. A wealth of concertante and chamber music works should be mentioned here, not least around twenty pieces for and with percussion to date, which have contributed to leading their author to enviable (and indeed envied) numbers of performances internationally.

I spoke of 'autonomous artistic will', but I immediately correct myself: it is enough to have touched Bertold Hummel's kind and humorous gaze once to realise that for him writing music is always also an act of humanity, to give his contemporaries and those born after him something that increases their share of beauty. Everyone who knows Bertold Hummel knows the softly discreet devotion with which he helps his young colleagues and the astonishing curiosity with which he - now Honorary President of the Würzburg Academy and member of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts - continues to seek encounters with the new."

I find it difficult, very difficult, to be reminded with every verb in the present tense in this text that this present no longer applies in this form. Bertold Hummel's death came quickly, it caught us completely unprepared. In April of last year he was still to be seen at Hirschberg Castle, magnanimously and benevolently observing the German bishops' encounter with a range of products of the musical avant-garde, not making much fuss about his sovereign capacity for discernment towards others. If I had realised that it was to be our last meeting, how many things I would have had to bring up! And how much I would have liked to look for his eyes, which always shone with so much confidence.

Bertold Hummel did a lot of good not only as an artist, but also as a teacher. in 1963, he was appointed as a composition teacher at what was then the State Conservatory in Würzburg and, following its transformation into the second Bavarian Academy of Music, was appointed professor. For eight years (1979-1987) he also held the office of president. Throughout his life, he was committed to contemporary music: he headed the Studio for New Music Würzburg, founded the "Würzburg Days for New Music" and worked for more than 25 years as an honorary member of the copyright organisation for composers, GEMA. Bertold Hummel was honoured many times for his works and services, including the Composition Prize of the City of Stuttgart (1960), the Robert Schumann Prize of the City of Düsseldorf (1961), the Federal Cross of Merit First Class (1985), the Cultural Prize of the City of Würzburg (1988) and, most recently, the aforementioned Art and Culture Prize of the German Catholics.

On the day before his death, in the Sprital, knowing that the end was very near, Bertold Hummel sketched a deeply moving piece for solo cello; he dedicated it to the outgoing managing director of the Guardini Foundation, Dr Hermann Josef Schuster, as a "last greeting" in the true sense of the word: as a "farewell" (the title of the work). Here, too, we can see the greatness of this man, who was able to transform even such a moment of existential crisis into a gift.

We miss Bertold Hummel, our dear friend, very much...

(Guardini Foundation e.V. - Annual Report 2002, Berlin)

In memory of Bertold Hummel

Karl Heinz Wahren

In memory of Bertold Hummel

We last saw each other in Berlin in July during the week of meetings of the GEMA Evaluation Committee for Serious Music. When I greeted him, his appearance seemed a little different, his face narrower and more asthenic than the year before. This may have been the temporary consequences of professional overwork. I paid no further attention to it, because in the first few days of the extensive and nerve-wracking assessment work, he took part in our discourse as lively and unerringly as ever. It was only on the third day that he complained of feeling unwell and eventually travelled back to Würzburg early.

The vibrancy of the moment displaces thoughts of what might be our last encounter, especially with an honoured, lovable colleague and friend. So the news of his death just four weeks later caught me completely unprepared and painfully.

We had known each other since 1971, when, as director of the Studio für Neue Musik Würzburg, he had invited our "Gruppe Neue Musik Berlin", which had been successful in West Berlin since 1965, to give a concert. This later developed into a collegial friendship, which deepened noticeably over time through meetings at the annual GEMA meetings, occasional joint concert performances and subsequent discussions.

From the very beginning, I was impressed by Bertold Hummel's behaviour towards his fellow human beings, which I would call benevolence. I have never experienced this trait so clearly in any other educated person. It is the ability to understand others and thus the talent to convey encouragement for life. Not in a naïve, uncritical manner. As a devout Christian, Hummel was a balanced and discerning spirit, but one that was also always ready for the necessary disputes.

However, the philanthropic side of his character, his understanding for those who thought and acted differently, his sense of agreement despite opposing positions - it sounds like squaring the circle - were unusual. At the same time, he could be strict, especially when it came to artistic dishonesty, contempt for his colleagues or exhausting vanity.

"As a composer, I feel an obligation to the community in which I live. My endeavour is to make a modest contribution to the effort to make the world a more humane and liveable place." This is the credo of Bertold Hummel, who was born near Donaueschingen in 1925. His paternal and maternal ancestors from Baden were craftsmen, but his father became a teacher, choirmaster and organist. He introduced his receptive and interested son to music at an early age. Later, as a headmaster near Freiburg im Breisgau, he gave his son piano lessons. His particular musical talent was specifically encouraged at the Oberrealschule in Freiburg through cello, harmony and composition lessons. When the pupil heard Bruckner's "Third" at a symphony concert, he was determined to become a composer. His participation in the boys' choir in performances of Parsifal at the Freiburg City Theatre cemented this intention. In Anton Bruckner and Richard Wagner, he chose two long-standing role models for his career. But first, following the demands of the National Socialist dictatorship, he had to put on the earth-brown uniform of the Reich Labour Service for pre-military training, only to march into the Second World War just six months later - now in olive-green Wehrmacht fatigues. He survived these steel storms physically unscathed; while still a prisoner of war in France, he began writing compositions for a prison camp band after the German capitulation in 1945. in 1947, he saw his homeland again, was able to continue his school education, which had been interrupted shortly before the start of the war, and completed his A-levels. He then immediately began his studies at the Freiburg University of Music, including composition with Harald Genzmer, his cello teacher was Atis Teichmanis and he studied conducting with Konrad Lechner. Hummel remembers this post-war era of the late 1940s as a time of "catch-up euphoria for the generation returning home".

In 1954, he went on an almost year-long concert tour of the South African Union as a cellist with a group of young musicians. There he also married his colleague, the violinist Inken Steffen. After his return, Hummel initially took up a position as a cantor in Freiburg and continued to perform as a cellist, including as a permanent substitute with the symphony orchestra of Südwestfunk Baden-Baden. His work as a composer was recognised with numerous prizes, including the Culture Prize of the Federation of German Industry (1956), the Composition Prize of the City of Stuttgart (1959) and the Robert Schumann Prize of the City of Düsseldorf (1960). He was appointed as a composition teacher at the Bavarian State Conservatory of Music in Würzburg in 1963, where he worked intensively in the field of contemporary music for over two and a half decades.

After Hummel was put in charge of the "Studio for New Music", he presented works by numerous young composers in his concerts, some of whose names have since become familiar to audiences throughout Germany. Hummel's cosmopolitanism allowed him to bring together seemingly incompatible aesthetic directions in his programmes and thus put the breadth of compositional creativity in the last quarter of the late 20th century up for public discussion. His flexibility in understanding stylistic contrasts was something he also knew how to convey to his students with psychological intuition, in order to awaken their mental alertness and the receptivity of their senses, thereby stimulating their imaginations.

His own ideal sets standards, and Hummel's aim was always to broaden his musical horizon of perception without being unfaithful to himself. In other words, he had now succeeded in finding a recognisable compositional style of his own. This was originally based on the neoclassicism of his teacher Harald Genzmer - and in turn his teacher Paul Hindemith. Having long since moved away from this, he had found his own musical expression through the influence of the French schools of the early 20th century, and indirectly also the New Viennese School. Hummel's inspirations were clearly influenced by the French composer Oliver Messiaen, whose concepts of tonal colour were realised in Hummel's compositions.

Of course, the composer Hummel always had to take his university teacher into consideration. In 1973, the Bavarian State Conservatory in Würzburg was transformed into the second Bavarian University of Music and Bertold Hummel was appointed full professor. he was finally elected President of this university in 1979 and was made Honorary President after his retirement in 1988. He had previously been elected a member of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts in 1982, was honoured with the Federal Cross of Merit 1st Class in 1985 and the City of Würzburg awarded him its Culture Prize in 1988.

Over the past decade and a half, freed from the burden of his time-consuming university duties, Hummel composed tirelessly and with inspiration, always in search of new expressive possibilities, which he then assigned to his very own musical personal style. "My view now, at the end of this millennium, is that after a century in which experimentation played a major role, the longing for a new discovery of language is gaining ground worldwide. In my opinion, a new aesthetic of plural possibilities will prevail against the orthodoxy of the respective "direction"."

In recent years, Hummel has travelled to numerous countries, including the USA, Russia, Australia, France, Austria, Switzerland, Poland and the Czech Republic, to take part in the many international performances of his works. The Conventus Musicus label has released an interesting selection of his compositions as a CD edition.

His compositional honesty is equal to his diligence. His oeuvre, which comprises over 200 works, did not prevent him from working in an honorary capacity for GEMA, the copyright society that is unique to us composers. For more than 25 years, he was one of the most responsible members of the extraordinarily important Evaluation Committee. He also taught his students about the vital importance of copyright for composers, encouraged them to attend GEMA's annual meeting and was always on hand at discussions when it came to the interests of serious music. Nevertheless, he remained reserved throughout his life, never stepped into the limelight and only represented where it was unavoidable. His inner equilibrium did not require the over-esteem complex that many composers had to compensate for the cult of genius that flourished in the 19th century and was increasingly lost to society in the 20th century.

His family, his lifelong companionship with his wife, his six married sons - five of whom became professional musicians and four daughters-in-law - and 17 grandchildren evidently gave him stability and the composure that he always radiated to the end in difficult "discussions", e.g. about GEMA problems.

His life's work as a composer leaves its mark on almost all musical genres and instrumentations. He explored the new compositional techniques of the 20th century, 12-tone music as well as serial techniques, jazz and the possibilities of electro-acoustic music. He used the discovery of percussion for our evening music as successfully as the timbre of the saxophone. Contemporary sacred music in particular found one of its most important, secularised representatives in him. When asked to characterise his compositional style, he replied: "I would describe it as a style of metamorphosis of everything that particularly impresses me from the musical world repertoire of the past and present; paired with a strong personal will to express - as a kind of creative eclecticism."

We mourn in equal measure for the composer and pedagogue, but above all for the endearing colleague and human being Bertold Hummel.

(from: Gemanachrichten NR: 166 3/2002, Berlin)

In memory of Bertold Hummel

An obituary

Michael Wernicke OSA

in memoriam Bertold Hummel

An obituary

I got to know the sons first: I sometimes went for walks with the youngest, the twins, who, as they proudly told me, were eight years old at the time. "My terrorists", their father affectionately called them, because they were wild boys, full of original ideas. Mr Hummel loved it when I told him how I bought them an ice cream. I asked the mate who accompanied them if he wanted an ice cream too. "No," he said. In response to my astonished question as to why not, he told me that he was Protestant. At Mr Hummel's request, I had to repeat the story several times, whenever there was someone in the company who didn't know it yet.

Mr Hummel loved anecdotes and was a great storyteller himself. At the Landvolkshochschule Wies near Steingaden, he spoke about a stay in the United States. He had been invited to teach American music students and perform his works with them. When he rehearsed a piece of music with them and saw that they were excited because the composer himself was standing in front of them as conductor, he said comfortingly and encouragingly "Don't be afraid! What comes, comes, what does not come, does not come." That was very German English, and Mr Hummel knew it when he described this experience. He was able to smile at himself, which is the mark of true humour. When he told this story, I laughed out loud, but at the same time it dawned on me that Bertold Hummel was a famous man, world-famous. And here we were in the Wies with a lot of young people who wanted to make music, amateurs for the most part. Mr Hummel, professor and president of the Würzburg Academy of Music, a widely known composer, was not above forming an orchestra with children and young people, practising with them for a week and occasionally letting them play a piece in front of the other participants. he called this an "indulgence", as it urged the young people to perform in front of others what they had painstakingly rehearsed. Towards the end of the week came the big indulgence: a public concert in the Wieskirche, where I, who am of limited musicality, was allowed to announce the works to be performed. But I also celebrated church services with the young and old musicians, because this Wies event was Catholic, initiated and organised by the Düsseldorf Youth House.

Speaking of church services: The whole Hummel family enjoyed playing music under my father's direction in the church of St Bruno for Christmas mass. At first, everyone joined in: The wife and children, the sons got married and pursued their careers elsewhere. The family ensemble became smaller and smaller. It was like an extended farewell symphony. Music and a church service. If I wanted to say that these were the two poles around which Bertold Hummel's life revolved, that would be wrong and yet not wrong again. In any case, I would be guilty of gross inattention if I were to forget that Bertold Hummel's wife, sons, daughters-in-law and numerous grandchildren had a large place in his heart. Music and worship - he hardly wanted to separate them. The meaning of creation for him, as the bishop reported at the requiem, was the praise of God. The silent praise of the inanimate creature, the rustling praise of the trees, the roaring, crowing, singing, bleating praise of the animals, the jubilant, humble, mournful praise of man, of man making music. For Bertold Hummel, praise of God was - in the spirit of Jesus - also a service to mankind. A saying hung in his study: "No man is there for himself alone, but also for all others." He believed in the power of music to make people happy, to heal, to enable them to express joy and sorrow, to praise God and thus find the meaning of life. And he introduced people to music. He did it humorously, cheerfully and modestly. "Anyone who thinks they are something," he wrote above the piano in his study, "has ceased to become something."

Shortly before his death, Bertold Hummel played the Advent hymn "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme" on a keyboard while lying in his hospital bed First in unison, then in a polyphonic movement. The second verse reads:

Zion hears the watchmen sing.

her heart leaps for joy,

she wakes and rises in haste.

Her friend comes from heaven splendid,

strong with grace, mighty with truth;

her light grows bright, her star rises.

Now come, you precious crown,

Lord Jesus, Son of God.

Hosanna.

We all follow to the hall of joy

And join in the communion.

Mr Hummel died on 9 August 2002, and I believe with confidence that he entered the hall of joy.

(in: St Bruno Pfarrinfo, Würzburg, September 2002)

Commemorative event on 27 November 2002

Martin Hummel

Martin Hummel, the composer's son, gave the following speech on the occasion of a memorial service on 27 November 2002 at the Hochschule für Musik in Würzburg:

Dearly beloved,

who have come together today to remember Bertold Hummel.

For most of you, my father's name is associated with his compositions, many of you have fond memories of his warmth and humour, some of you have happy memories of him as a colleague, mentor or friend.

For our family, he has been removed from everyday life. Whether it's the children painting Grandpa's flower-decorated coffin at school or us adults who - so soon after his unexpected death - are repeatedly overcome by deep sadness in our everyday lives: we are trying to get used to the fact that we can no longer recognise his voice, his movements and his touch.

In this difficult time for us, however, we realise that compared to some other people who have to come to terms with such a difficult loss, we can do so in a large community of like-minded people.

The many people who gathered for his impressive requiem in the cathedral, the many musicians who spontaneously approached us and wanted to honour the deceased with their art in many places: They help us to melt the pain into song - as Tagore put it so beautifully.

Today, on his 77th birthday, we are particularly grateful that the University of Music is organising this concert in memory of Bertold Hummel as a matter of course. We are delighted that so many students were prepared to engage with his work together with the teaching staff.

This is exactly how my father understood music - as an art that unites people. Music as an expression of friendship and affection.

We were pleased that the numerous obituaries recognised that he saw his composing as a modest contribution to a more humane world.

There is hardly a composition that he did not dedicate to someone, whether it was a child, a great musician or the good Lord.

He knew for whom he was writing the pieces. When his grandchild Fabian began to play the violin, he composed a little violin concerto for him - in the first position, of course. When the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra commissioned his "Visions after St John's Apocalypse", something more was required in the violins.

Some of his composer colleagues probably turned up their noses at this understanding of the work. But he felt part of the community. "No one is in the world for himself alone, he is also there for everyone else." This saying still hangs above his piano today.

There was often a specific reason for a composition. I still remember well how he was shocked on 4 December 1976 when he heard the news of Benjamin Britten's death on the radio. He withdrew and after a few hours he played the Adagio we heard at the beginning on the piano.

The rapid mental deterioration of his life-affirming friend Dietrich von Bausznern shook him to the core and immediately inspired him to play "in memoriam".

He wrote the "Ave maria" (in the German version) in 1993 under the impression of the death of his sister Erika. A year before his death, he returned to the composition and now considered the Latin version to be the more successful one.

I think you can hear the spiritual clarity in this work with which he was able to approach his own death.

In the last years of his life, quite contrary to his habit of leaving pieces unpublished forever, he placed them with various publishers and revised earlier works.

The publication of the "Tastenspiele", which he repeatedly composed and performed for his grandchildren's birthdays and christenings, was something he took in hand with unusual speed.

He composed the texts for a song cycle based on bizarre poems by Hermann Hesse, which I had recommended to him years ago, as his last work.

Before I drove him to the hospital, he discussed the final corrections with me. As a rule, he always agreed with my suggested order of the songs, but this time it was important to him that the following poem should be at the end:

Instruction

More or less, my dear boy,

After all, all human words are a sham,

Proportionally we are in the nappy

Most honest, and later in the grave.

Then we lie down with the fathers,

Are finally wise and full of cool clarity,

With bare bones we rattle the truth,

And many a man lies and prefers to live again.

He experienced this ambivalence of death clearly in his last days.

On the one hand: the rapidly progressing physical decay, which he accepted with stoicism:

When it was announced that he would be receiving blood transfusions, he replied: please not from a pop singer.

On the other hand, his mental vitality clung to life:

Between examinations, he used the time to set Christmas carols for two melody instruments and gave final instructions on a sketch sheet for a violoncello solo shortly before his end.

Some of his works will probably still be played when those of us who knew him are no longer around.

This is a beautiful vision for us.

In gratitude for the reverence and friendship that my father and his work have always received, especially here in this house, we would like to leave his entire printed oeuvre (185 volumes) to the university library and we hope that in the future one or two people will take the opportunity to understand the musical cosmos of this life's work.

The last book my father read was "The Speeches of Seneca".

There he emphasised the following:

Sift through the days of your life - and you will see how few remain on your account that belong to yourself ... On the other hand, he who lives rightly, utilises every moment and arranges each day as if it were the last, lives in the eternal now.

There are enough teachers in the arts and sciences, but you have to learn to live yourself throughout your entire existence until you become a master.

So many people are pushing forwards and suffer from the longing for the future, from the weariness of the present. You are busy, your life is hurrying along; in the meantime death will appear, for which you must have time, whether you like it or not ...

The greatest obstacle to a happy life is the expectation that depends on tomorrow.

You lose today; what lies in the hands of fate you try to organise; what lies in yours you let go. How wrongly you think!

Thank you for your attention.