Concerto for percussion and orchestra (op. 70, 1978)

I. Adagio, II. Allegro vivace, III. Lamentation, IV. Finale-Vivace

Solo percussion: vibraphone, marimba, snare drum, 2 bongos, 2 tom-toms, 5 temple blocks, African slit drum, ratchet, 5 cymbals, rivet cymbals, Chinese cymbals, gong, tam-tam, triangle, 3 cowbells

Orchestral instrumentation: 3.3.3.3 - 4.3.3.1 - timpani, percussion <3 - 4>, harp, strings

Duration: 30 minutes

Jeff Beer | Regensburg Philharmonic Orchestra | Thilo Fuchs

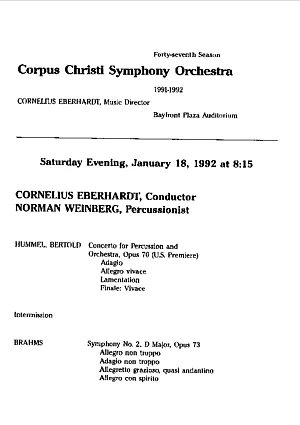

Norman Weinberg | Corpus Christi Symphony Orchestra | Cornelius Eberhardt

Nesma Abdel Aziz | Cairo Opera Orchestra | Jacek Kraszewski

Peter Sadlo | Nagoya Philharmonic Orchestra | Ryusuke Numajiri

Mark Lutz | Queensland Symphony Orchestra | Gerald Krug

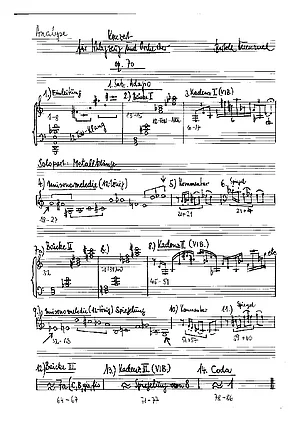

Score: Title: Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra op. 70 - Length: 112 pages (before shortening 130 pages) - Dated: I. - II. 23 August 81 / III. 1.10.81 IV. / Composition finished on 11 Oct.81 Dorfgastein / Instrumentation finished on 11 March 82 in Würzburg - Location: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Munich

Piano reduction: Title: - - Length: 70 pages (after abridgement 62 pages) - Date: X. 84 - Location: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Munich

Schott Music International (loan material)

Piano reduction for sale ED 7830 / ISMN: 979-0-001-08122-1

op. 70, I. Adagio

op. 70, II Allegro vivace

op. 70, III Lamentation

op. 70, IV Finale vivace

Sadlo demonstrated the melodic fireworks that are possible on the marimba and vibraphone as a soloist with the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester at the Konzerthaus. Bertold Hummel's virtuoso "Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra" is a showpiece for the "master of the clappers". With sensitive antennae, he explores the sound worlds of various cymbals in the Adagio, which he makes vibrate with soft tremolos. His mallets bounce over the marimba at breakneck speed like a ping-pong ball.

Peter Sadlo achieved great success as a soloist with the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester in the Konzerthaus. Sadlo makes real music with cymbals and bongo, gong and bell, xylophone or vibraphone. He not only demonstrates that the times when percussion was merely used for loud background music are over. In Bertold Hummel's "Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra", he has a work under his powerful, nimble hands that is worth the performer's effort. Hummel begins with Bruckner tones. Trombone pathos dominates in an adagio. The percussion counter this with a long resonating echo and the muffled drone of the bass drum. It often takes the lead in the other three movements. The rattling and clanging, wooden tapping and dry banging, the hissing of the cymbal strokes develop into a colourful speech of sound. With the drum roll of a funeral march, with bell singing and the sound of bells, the music passes through the Great Gate of Kiev. There are hints of Bartók motifs. But Hummel's opus remains original and easy to grasp.

The audience gave thunderous applause. They were amazed and enraptured by the brilliance of this music ...

Hummel has composed a genuine concerto in which the percussion takes the place of the classical solo instrument, in an alternating dialogue with the orchestra, with its own cadenzas. This is a rare occurrence and the young percussionist Jasmin Kolberg (29) utilised the available space with intense musicality. With her virtuoso and sensitive percussion technique, she countered the symphonic, sometimes threatening, sometimes plaintive gestures of the orchestra, giving them surprising colours and rhythmic figures as suggestions with her cadenzas. She even managed the expressive feat of creating a "lament" using only percussion instruments, which then dissolved into a whirling vivace. The audience applauded vigorously and stamped their feet.

The composition itself is a masterpiece of musical ideas and their realisation with percussion instruments.

Hummel gives the musicians what they want. Opportunities for the strings to bathe in a rich sound, the chance for the brass to make their mark. And the musicians of the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie did not miss the opportunity to trace Hummel's symphonic developments with great intensity. Even if they had to take a back seat to the dominance of the percussion in many places, they made an enormous contribution to the popularisation of this composition under Toshiyuki Kamioka's precise direction.

The most haunting movement is the Lamentation, an "In memoriam" piece for Dimitri Shostakovich, whose musical tone letters D (E)S C H are based on a kind of funeral march ...

The love of the monumental is also evident in Hummel's Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra, although completely different, meditative, almost lyrical tones could also be heard here for long stretches. The long solo at the beginning of the second movement was fascinating, not only because of its high demands on the soloist's technical ability, but also because of its highly interesting and imaginative interweaving of rhythmic and melodic structures. This also applies to the rather meditative third movement, entitled "Lamentation", which the percussion also begins without orchestral accompaniment. Almost imperceptibly at first, this meditative mood transforms into increasingly threatening, dark drama, which finally dissolves into quiet despair. The concert ends with a lively finale, for which Peter Sadlo received far more than polite applause.

A concertante competition between soloist and orchestra, following the basic principle of a solo concerto ...

The audience was highly enthusiastic about the work ...

With great skilfulness and effect, Hummel used half tonally difficult, half powerfully pathetic means reminiscent of Rolf Liebermann's Concerto for Jazz Band and Orchestra, which enabled the percussion soloist to showcase himself to great effect.

J.S. Bach would certainly have enjoyed this concerto for percussion and orchestra by Bertold Hummel, whose second movement plays with the famous B-A-C-H motif in a highly original way. Bach himself even composed strongly rhythm-orientated music in his church cantatas, which earned him harsh criticism from pious Christians during his lifetime ("dancing rubbish"). In his concerto for percussion and orchestra, Bertold Hummel draws an arc from B-A-C-H to the twentieth century with the tone sequence D-S-C-H for Dimitri Shostakovich. A music-historical homage of great musical expressiveness, seriousness and depth. This work, premiered in 1985, is interpreted congenially by Peter Sadlo on his new CD "Percussion in Concert". Sadlo is the masterful playmaker when, together with the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra under Wolfgang Rögner, he puts everything the percussion has to offer into action. The term "virtuoso" is just a tired auxiliary word here. You can't help but think of those Indian deities who have more than just two arms at their disposal when you listen to Peter Sadlo using wood and skin to make his battery of percussion instruments, including vibraphone and marimba, resound. Peter Sadlo offers percussion that could not be more effective, exciting and tonally mature, but which nevertheless does not stop at pure effect. Bertold Hummel's Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra is the central work on this CD.

Jürgen Seeger

As he writes, Hummel wanted to try to give qualified percussion soloists, of whom there are now a considerable number, the opportunity to perform with the orchestra that other instrumental soloists have in large numbers. He has succeeded, but he needs the best of the many good percussion soloists who can play for him. Jeff Beer is one of them. The fact that the percussionist, who also enjoys an international reputation as an avant-garde composer, was a pupil of Bertold Hummel certainly helped the premiere. In his work, Hummel very consciously differentiates between percussion instruments with fixed pitches such as the baton instruments, vibraphone and marimba, and others with non-fixable pitches such as cymbals, tom-toms, triangle, gong and others, especially the wooden blocks in various sizes, which are graded according to lighter and darker tone colours. He leaves the tunable timpani and bass drum to the orchestra. In this concerto, the opinion that "concerto" comes from "concertare = to quarrel" is finally reduced to absurdity, because here only the derivation from "conserere - French concerter - to join together" applies. concerter - to join together": if there is a unity of soloist and ensemble in a concerto, then it is here. This in and out of unity is the genius of this concerto. Hummel makes free use of the tonal space and operates with compositional means that the symphonic tradition of the present has handed over to him for his own composition. This elevates his work far beyond pure avant-garde sound and makes it accessible. The correspondence of pure, indifferent sound, such as the gongs and cymbals at the beginning, to iridescent orchestral clusters, alternates with the virtuosically handled passages of the bar instruments with succinct unison themes of the strings and winds, which grow out of and return to the unmistakable musical diction of his teacher Genzmer and his teacher Hindemith in Brucknerian dimensions.

The virtuosity of the soloist is largely reflected in the second movement, which is also more characterised by the motor skills placed on the drums and finally contains the great "cadenza", an extensive percussion solo that develops brilliantly and, after a meditative phase, leads into a rapid coda. The soloistic idea leads into the third movement, entitled "Lamentation", which is then very variable in mood and reaches a pastose climax. The striking strings are heightened by striking, almost chorale-like, heavy brass in order to allow the funeral march-like drum passages to linger in the memory after an almost abrupt conclusion in an almost fading into nothingness in their alternation with the wide melodic arcs of the orchestra.

A fourth movement follows, which takes up many of the elements of the preceding movements, especially the first. This is a formally well-conceived work in itself, but it also harbours its own problems: after the fulminance of the second movement and the high density of the third, a very short overall coda, if there is such a thing, would perhaps have concluded the work more effectively than this relatively extended fourth movement.* Although it plays the vibraphone in particular to the fore with great virtuosity and thus takes on an almost rondo-like character, overall it seems too long. After the intense three preceding movements, the sounds are at times overused, they wear out. Somehow, however, such an impression also shows that the concertante possibilities of the percussion instruments are obviously limited, since formal and thematic fascination can be better created through the combination of melody, form and rhythm than through too much "just" sound. Hummel wisely endeavoured to limit this to a convincing degree. The work made a great impression and is likely to make its way through concert halls.

Any conductor who has a Paganini of percussion like Jeff Beer as a soloist is lucky. Tilo Fuchs worked with him and an orchestra that was perfectly prepared and played with the utmost concentration and differentiation. Conductor and orchestra have justified the confidence in the première.

Franz A. Stein

* Hummel made a few cuts to the score after the premiere.

By his own admission, Hummel wrote the Percussion Concerto, which was composed between 1978 and 1982, primarily as an addition to his repertoire. With his opus 70, however, he also succeeded in creating an original work, which, in a conventional four-movement sequence and sound reminiscences of Webern and Shostakovich, for example, provides attractive and captivating music for an unusual set of instruments: The soloist has to find his way between vibraphone, marimba, snare drums, bongos, tomtoms, temple blocks, cymbals, bells, gong and triangle, and in Frank Thomé, a musician was chosen who succeeded in this with dreamlike confidence. Hummel formulated the soloist part - especially in the fast-paced second movement - as a highly virtuosic dialogue with the orchestra, a demand that the musicians met in a captivating manner.

Claus-Dieter Hanauer

Although the percussion has increasingly emancipated itself as a solo instrument in recent decades, the chances of a percussion soloist finding a place in the subscription series of concert orchestras are relatively slim. In my opinion, the reason for this is less a lack of high-calibre percussionists than a lack of relevant literature. My Percussion Concerto op. 70 is an attempt to address this situation.

In 4 contrasting movements, metal, skin and wood sounds as well as the pitch-fixing sounds of the marimba and vibraphone are assigned to the solo part in different movement sequences ranging from pure, partly meditative sound play to virtuoso figuration.

The normal orchestra (triple woodwind) not only has an accompanying function, it is closely interlinked with the sound and movement projects initiated by the percussion, but is also given independence in larger symphonic developments.

In the first movement - an adagio with an introductory character - metal and vibraphone sounds are predominant. They comment on an expansive orchestral gesture that appears twice in different structures and clearly organises the movement.

The Allegro vivace is a burlesque interplay between solo and orchestra of urgent motorisation. Towards the end, it gives the percussion room for an extended cadenza, and a brief coda concludes the movement.

The Lamentation - an homage to Dimitri Shostakovich - has meditative traits. Various episodes develop from a solo cadenza. A large-scale symphonic build-up leads to a climax, which is situated in the so-called golden section. A swansong leads back to the opening mood.

In the finale, the virtuoso element is in the foreground, which is mainly assigned to the marimba. Quasi-improvisatory interludes interrupt the musically propulsive movement.

Bertold Hummel

On Bertold Hummel's Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra op. 70

The disintegration of unity within contemporary music is reflected not least in the fact that the musician is in danger of falling by the wayside. The unity between the musical gesture and the weight of the statement seems to be undermined. The debate about whether new music belongs in the subscription programme or whether it would be better to look for alternative spaces also essentially addresses this dilemma. In the meantime, however, young performers are growing up who feel - at least in part - let down by their fellow composers. The latter demand a maximum of technique, flexibility and concentration from orchestral musicians, while the need for comprehensive presentation is given far less attention, which is particularly true for instruments that have been neglected by tradition. The percussion is one of them. Although important works have been written for it in soloistic treatment (or as percussion group compositions) since Edgar Varese or Karlheinz Stockhausen's "Zyklus", hardly any of them have the chance to reach the "normal concert subscriber". Of course, instrumentalists and composers have repeatedly pointed out this shortcoming, but they have been condemned as outmoded "musical entertainment". The shortcoming remained, however, and in Germany this gave rise to a compositional trend that was particularly orientated towards the work of Paul Hindemith. Today, as the judgements that were once pronounced with irrefutable conviction have begun to waver and are even ridiculed by younger composers, this movement is once again being listened to far more resolutely. Bertold Hummel, who can be regarded as Hindemith's "grandson" through his teacher Harald Genzmer, also belongs to this movement.

His many years of teaching at the Würzburg University of Music brought him into close contact with Siegfried Fink and his percussion class. This exchange of experiences and the almost insatiable need for new percussion music there led to a series of compositions, the most central of which is probably the Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra, begun in 1978 and finally completed in 1982. Bertold Hummel wanted to expand the opportunities for integrating percussion playing into the concert programme; the success of well over twenty performances to date, even beyond Germany's borders, proved him right.

These aspects determined the compositional structure. The piece is in four movements and, with the demonstrative gesture of a concertante work, attempts to explore the sound ranges of this extraordinarily versatile instrument (the concerto calls for vibraphone, marimba, drums, bongos, tomtoms, temple blocks, slit drums, cymbals, gong, tam-tam, triangle and alpine bells for the solo instrument). For example, metallic sounds (tam-tam and cymbals) and sound gestures in the vibraphone in the slow first movement create a meditative mood, which is echoed in the third movement "Lamentation". This contrasts with the impulsive effect of movements two and four, which emphasise motor skills and burlesque playing, with space created in the second movement for a large-scale percussion cadenza. The musical language here moves in a space of extended tonality with a preference for shifting fifths and chromatic blurring. This also characterises the vividly shaped, gesturally rich theme, which gives the concerto an inner coherence across the movements. At the centre, however, is the charm of the playing, the virtuoso and suggestive treatment of the percussion, to which the orchestral writing is also subordinated in a supporting or counterpointing manner.

In this sense, Bertold Hummel's percussion concerto is to be understood as the development of a body of literature that has yet to be fully realised.

Reinhard Schulz (in: Munich Philharmonic Orchestra: Programme booklet for the 7th subscription concert, May 1989)